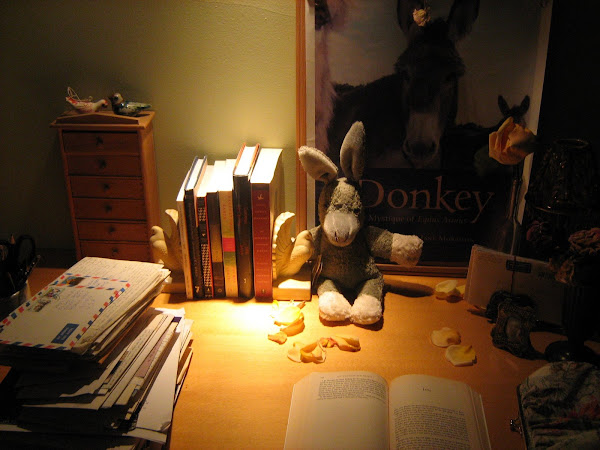

Well-Read Donkey Bookshelf at Kepler's with guest bloggers books and their reading recommendations

Earlier this month, I had the good fortune to be on a panel in Chapel Hill, NC, with Robert LeLeux, who wrote The Memoirs of a Beautiful Boy and is as moving and amusing in person as he is in his memoir. When I first got word of the pairing with Robert, I considered this another one of those mango-and-peanut-butter author mixes for which literary festivals are famous. For example, I was recently on a panel about the future of Southern Women Writers, though I was born in the Arizona desert, lived a decade overseas, now reside in Brooklyn, and have no more than passed through the South. (I like the South, though, and adore fellow panelists Janis Owens and Cassandra King. I sometimes imagine the people who create these panels gathering around a wooden table with a few dozen bottles of wine, a dart board, and all of our names on printed sheets, intent on getting a laugh somehow during the intimidating and grueling process of organizing a festival for writers and readers.

On the face of it, Robert and I are very different writers. My four books are novels, often on serious topics and with an international bent. His is a poignant American memoir and in some passages, a laugh-aloud look at life.

Yet our panel topic was passion, and its place in our work, and on this we found a lot of common ground.

Beginning and not-so-beginning writers are told to write what they know. Some have amended it to say: write what you’d like to know. But perhaps the adage actually should be: write what you care about. Deeply. Write what wakes you up at night, what you don’t understand, what makes you laugh so hard you cry, what you wish you could turn away from but can’t. Write to discover, not to expound.

The first reason to incorporate those deepest personal concerns in our writing, be it fiction, non-fiction or memoir, is that it invariably makes the work stronger. If this is the stuff that matters to us, we stand a better chance of getting our readers to care also.

But the second reason is actually more important, in my view, if more private. It is very old news by this time that publishing is in turmoil, uncertain what the future—even six months from now—will look like. Content has been devalued. Websites that demand writers to write deeply, or research broadly, or report diligently, still have no business model in place, and thus no way to pay those writers for their work, or even ensure their own continuation. In this climate, editors often find it safest to reject a manuscript. A good friend and dynamite literary writer recently told me she’s having trouble publishing her next novel because her “numbers aren’t good enough.”

And yet, many of us can’t stop writing. We write when happy or sad, we think in stories, we’re on the hunt for the subtext and telling gestures, and we feel compelled beyond our control to search for the fresh, well-turned phrase.

For some of us, in fact, writing—and reading—is spiritual work; it’s how we interpret our world, understand our lives, maybe even try to make ourselves better humans. To achieve that, we have to write about what makes us avidly curious or angry or frightened. We have to write with an unwillingness to settle for simple answers, an enthusiasm for embracing flaws, and the desire to see deeply and non-judgmentally into the Other.

This is what creates writing that is honest and authentic, perhaps with a shot at getting published, maybe getting read, maybe briefly impacting another life. And sometimes, if we’re very lucky, it draws us to others (like Robert, or my inspiring editor Fred Ramey at Unbridled Books who share our sentiments about the potential of words to take flight and connect.

It is also the work that can continue to feed us emotionally and psychically during the days and months of countless revisions or rejections, when the paragraphs buck us or our characters have fled underground or the computer eats a chapter or someone wants to discuss our numbers, when we’re distracted by loss or joy or fear and the only way forward, after all, is to write, write again, keep writing about what makes us passionate.