Joan with her granddaughters Brittany and Bella (right to left)

A wise friend suggested I list some of the ways in which the calling of writing makes one happy—to ward off evidence that the work brings an apparently limitless supply of frustration, loneliness, difficulty so cunningly intricate it approaches a kind of Escherian sublimity, and in result, anguish.

An answering image comes to mind, from a silly Tom Hanks movie called "Splash." In it, Darryl Hannah plays a modern mermaid, whose fate is to own a pair of (drop-dead) female legs on land but, as soon as she’s in water, to manifest a glorious, scaly, powerfully-tailfinned bottom half. One scene I remember shows her filling a tub, with the bathroom door locked. The next moment we see her blissfully reclined in that tub: a brief retreat from the bewildering demands of humans, her fabulous tail flicking once or twice in peace and contentment. The bath has clearly restored an ineffable, deeply right state of things, down to the DNA.

It feels like that to be sitting at the keyboard.

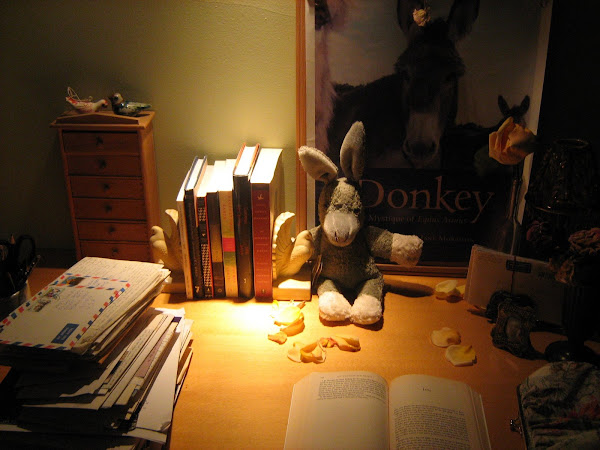

I’m pretty sure I was imprinted to respond this way by my late father—a teacher who spent endless hours in the simple den he’d built behind our Arizona home. There he’d installed air conditioning, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, a first-rate sound system, and a big desk made from a wooden door placed on two low filing cabinets. He burned incense in a little brass Buddha, played jazz, classics, Broadway, and opera on the stereo, and typed his head off—a rich, staccato music of its own, filled with the intensity of his thinking—at a Royal Portable typewriter which later became my high school graduation gift.

The objects, the tableau, the sounds and smells (sandalwood, sweat, books)—shaped me early, at what I’d have to call soul level. Anyone who’d known my father, and then lived to see my studio out behind our house today—its big old wooden desk, shelves of books, Glen Gould on the CD player—would be entitled to laugh, because it would appear I’d done my best to copy my father’s retreat in every detail (except the incense). Most tellingly, to "assume the position"—sitting at the desk, staring at pages or screen—still gives the instant, deep comfort of the fetal curl.

Here are similar moments, gathered in a free-association search:

- Intervals at the desk when it occurs to you that you don’t know what’s going to happen, and that you’re writing to find out. Your heart pounds.

- Finding a way through heinously painful passages that must nonetheless be told: being “accurately alive” to the framed experience, to borrow a fellow writer's words. Getting it right gives something and eases something, but I won't call it psychotherapy, because it's not.

- Rereading work after a long time away from it and feeling extreme relief to see that it still reads as it should.

- Feeling not ashamed but loyal, even grateful toward prior work. It was necessary, and you can stand by it.

- Driving alone in the car, and suddenly understanding what the title must be. (Titles are such a strange and delicate business—you seek them as if setting out to bag Tinkerbell in a butterfly net.)

- Swimming or walking or washing dishes or sweeping or staring at nothing, and understanding, of a sudden, what needs to happen next.

- Going into a piece of work to clean it up, and in some blessed flash seeing where certain material can naturally fall away. The unnecessary words almost turn a lighter shade before your eyes.

- Getting up from the desk as if from a long sleep, with only the dimmest sense of how much time has passed.

- Being unwilling to stop, even to eat. It happens. (And I really, really love food.)

- Bothering to turn on the light at night to jot the needed words, even if they wind up getting dumped. (You may insist you can remember without jotting. Good luck with that.)

- When life appears to be rocketing to hell and the known world exploding into gumball-sized shards, you can begin to write about it. The act is private, costs no money, keeps you company, gives validation, context, and some degree of control: a precious, slim tether to the sanity you feared for.

- Images and words surface like golden carp: from memory, from an odd photograph, from dreams. A kid’s face. Camellias in half-decay. A dead robin. A painting. An argument on a beach, long ago. A phrase—fitting the need to hand like a little key.

- Weirdly, there’s even satisfaction in getting stuck. It's a signal you’re underway. Somehow you'll dig out, or wander accidentally through a side passage—often unaware you did, until later. There’s excitement in the trust you learn to place in that process, in making yourself receptive to it.

- Stumbling into reading that helps, in some way, what you’re working on.

- A note arrives like a “message in a bottle,” telling you someone was reached and moved by your work.

- You send a note to someone whose work has reached and moved you, and (as frosting) receive a warm response.

Many of the above sound like the habits and consolations of a junkie: while the comparison’s a bit violent, it may not be completely inaccurate. But the tradition—of needing a writing life to survive—emerges from a long, distinguished, and not-so-distinguished past. Flaubert called it “a dog’s life, but the only life worth living.” Somerset Maugham said that after a good day’s writing, regular life struck him as “a bit flat and pale” by comparison.

I recall a "Saturday Night Live" sketch years ago, showing a couple strolling happily through a city park. As they did, a voiceover declared quietly, “These two people have not used any commercial product to make themselves more attractive to each other.”

In the same spirit: none of the above-described pleasures has much to do with publishing.

Joan Frank