Belle Yang Interviews Belle Yang

Before we begin today's Q and A, please click here to watch this 4 minute film in which I am drawing a graphic novel page.

Q: Ms. Belle, are graphic novels all fiction?

A: Well, Belle, this area of art/literature is still being defined as it develops, but I asked my friend the librarian Ruthie Pennington Paget who is my go-to gal pal. This is what she says:

Comics are non-continuous, short stories that you find in a newspaper.

Graphic novels are book length, but they are their own format, which uses the methods of movies for presentation. They are the fiction format.

Graphic memoirs are a non-fiction genre of the graphic format.

The graphic style is a new format with fictional and non-fiction content.

Graphic style = cup. Non-fiction and fictional work are different kinds of ice cubes.

So, you got it? I am actually more rattled. I’ve read “Graphic Novels for Dummies” and it says graphic novels encompass fiction and non-fictional works as in memoirs. And some creators would be outraged to be called graphic novelists when they prefer the aesthetic simplicity of being creators of comics. Some just want to be called cartoonists. Manifestos have been written about what comics should mean. Manifestos? I thought they were only for Communists. Is Communism the root of all comics?

Q: Ms. Belle, what are a few of your favorite graphic novelists

Okay, the obvious ones are Art Spiegelman and Marjane Satrapi. Then there is Alison Bechdel’s “Fun Home”—oh, she is just so literary and laugh-engendering even in as quirky a setting as a funeral home. How can you get literary in a comic book, you ask? You can. She does and I do or at least I try to be.

There are historical comics like the Canadian Chester Brown’s “Louis Riel.” Now that’s an area I want to see grow—biography and history. Comics grow up.

“Stitches” by the Caldecot bemedaled David Small. Josh Neufeld—and I am raring to get my hand on his “A.D. New Orleans after the Deluge.”

There is Joe Sacco’s journalistic approach in “Palestine” and “Gorazde.” He’s great, even if his characters were drawn by an overzealous dentist.

Seth’s “It’s a Good Life if You Don’t Weaken,” about the main character’s obsession to discover the past of a dead New Yorker cartoonist. Seth's drawings are loose-limbed and stylish. Yes, some people get to go by one name because they are special.

Oh, not to forget David B.’s “Epileptic.” He’s French, so he gets to be just David B. (That’s Daveeeed to us uncouth Americans.) His drawings are stunning, marvelous. They make me wish I had made them. His story is painfully personal, about life with a brother who suffers grand mal seizures. Their parents’ attention is focused on the child with the problem. You get the picture. David has to live with the horrid N word: Neglect.

And I could tell you about the graphic novels I don’t love, but I always stop myself from being negative about another maker’s opus. This is my pet peeve: if it’s a bad book of any genre, it will die a natural death. Don’t throw dung at it. We need to review the good ones. Leave room for the idea that all your taste may be all in your buds?

Q: How did you choose the comics format?

A: It jumped out at me in a dark alley at a dead-end. It truly did.

I lived in Japan as a child and was devouring the telephone book-sized manga for girls and came to the US in 1967 wearing my favorite manga character shoes. Now in middle age, the manga phenomenon has washed over this continent like a tsunami.

As I mentioned in yesterday’s Well-Read Donkey post, I had a tough time selling my prose book with full color illustrations. In the eleventh year of my struggle, I reconnected with Alane Salierno Mason, my former editor at Harcourt Brace. She had moved to WW Norton and Company, and she suggested I take a look at Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis.” I did, and KAPOW! I was knocked over madly in like with the comics format all over again. I said, hey, I can do this, and do it well. So I turned my prose work into captions and dialogues, drew the pages in panels of art then showed them to Alane. Norton offered me a contract in the fall of 2007.

Q: Why do you work in black and white. Are you giving up color?

A: Ms. Belle, you know very well this question sends me into a tizzy.

As far as I can remember, I've loved black and white art. It began with black crayons on white sheets of paper on the backs of mom's students’ exams. When someone mentions comics, my mind flies to black and white inky panels, not color. Black and white has it's own set of parameters and design issues. Black on white is ecstatic. The two "colors"--one being the total absorption of light and the other, the throwing off of all light--are polar opposites. It's thrilling, its ecstatic, it's exhilarating. It's drama and conflict. Durm und strung.

Think about the first mark you make on a pristine sheet of paper. The abrasion of the black crayon or pencil is like an explosion in the cosmos, the moment when matter comes into existence.

Q: Ms. Belle, how should someone new to the graphic novel approach the reading of the first one?

A: I am always surprised by this question, because I learned to read manga when young, so it’s as natural to me as eating rice. You can do it any way you like: read it fast and come back to study the details. Or linger over each panel until satisfied and go on to the next. I can’t begin to break down my eye-brain functions, but I imagine I scan the panels and the entire page.

A graphic novelists like Chris Ware in his “Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth” asks us to scan the whole page, because he wants us not to read in the usual way of moving our eyes left to right and top to bottom. He requires us to take in the whole and then home in on the details within the panels. You eyes will get a lot of exhausting and exhaustive exercise when you read graphic novels. It’s not kid’s stuff. Oftentimes, you have go back to find the trail of white pebbles, like Hansel and Gretel, in order to find your way.

And no, you are not stoopid if you missed it the first time round. Reread, reread and reread.

Q: Why did you use a brush and gouache instead of markers or pen and India ink?

I’m Chinese. Chinese love the brush. Therefore, I love the brush. Chinese culture is inseparable from the brush, since Chinese calligraphy is defined as the Mother of all arts. (I’ve heard Westerners refer to calligraphy as the art of the dunce. Hey, don't frown at me: I didn’t say it.) The brush can be supple or energized. It is able to express the artist’s every emotion, whether it be peace, rage or elated trembling.

With gouache, an opaque watercolor, I can get the darkest velvety black. India ink can crack. It’s not as supple after it dries on the Bristol board and causes the paper to warp. Nothing uglier than warped art.

Q: Why do you say the Chinese horizontal scroll is like a pre-modern motion picture. How does it relate to the graphic novel?

When you go into Asian museums, you might see a horizontal scroll unrolled in its entirety under glass. This is the wrong way to look. Horizontal scrolls were hand-held devices. Intimate. You unroll a section to the left and roll up what you’ve seen on the right. It’s as if you are riding on the back of a donkey and you get to travel the landscape, entering the mountain, descending into a village, crossing a bridge, getting into a boat to float downstream . . . the boat goes over a waterfall (Uh, just checkin’ to see if you are still with me.)

This is exactly what I try to show the reader of a graphic novel. I take my reader into the landscape of my story. And I might add that scrolls have lines of poetry written directly into the silk or paper, just like captions in a graphic novel.

Q: Why are you nuts about this format?

A: Because it’s perfect for me. In my prose books, the two-dozen pieces of art got lost. In my children’s book, the art was dominant partner. In graphic novels, words and images come together in a perfect balance and neither overwhelms the other. And how cool is that to be make ice cubes to fill a largely unfilled cup. My cup runneth empty is a good place to be.

Q: What are you going to blog about tomorrow, Ms. Belle?

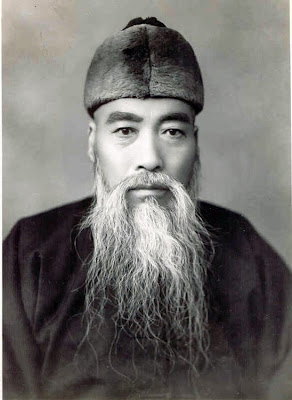

A: I’m taking you on a photographic visit of my workspace and the tools of my trade, which includes empty, white tofu containers. And the latter has zero to do with being Chinese. I also want to show you family pictures of ancestors. But I have 24-hours to change my mind.

I will be at Kepler's at 7:30 P.M. July 8th talking about the process of making a graphic novel. Please join me.

I will be at Kepler's at 7:30 P.M. July 8th talking about the process of making a graphic novel. Please join me.